Did you dress up as Sherlock Holmes when you were eight years old? Well, this week's Interesting Interview did! Soren Eversoll met the Great Detective at an early age and never let go. He was a member of The Norwegian Explorers of Minnesota before he could drive, and recreated 221B in his parents' house so well that the Twin Cities' newspaper did a story on him.

But what I find really amazing is that Soren's interest in Holmes has never left him. How many of us can think of things that we found interesting as kids but faded away as we grew and life offered new opportunities? In fact, Soren, now a college student, presented at last month's Lone Star Holmes conference in Dallas. So let's hear from a Sherlockian who definitely keeps those Holmes fires burning, Soren Eversoll!

How do you define the word “Sherlockian”?

A Sherlockian is, most simply put, a person who loves Sherlock Holmes and actively pursues that love. I think that this does require some familiarity with Conan Doyle’s stories, though this does not need to be comprehensive and should be something a person fascinated with Holmes would want to do anyway. The world of Sherlockiana has exploded since the old BSI Morley days, which I think shows that Holmes has the legs to withstand changing consumer appetites and should be celebrated. Turning up one’s nose at someone who’s entry point is the BBC show, which happens to be most of my generation, is corrosive to the whole idea of passing the torch forward and letting Holmes be Holmes for a new set of devotees. Nonetheless, a good Sherlockian might then direct that person towards the canon, as it is the foundation for everything else and a great read anyway.

Overall, however, I think a Sherlockian is just a person who puts down whatever form of Holmes content they have been consuming and feels that enjoying it is simply not enough, that they need to make something in response, or collect, or seek out others who feel the same way. It is that active pursuit, I think, that captivation with whatever lit the first spark, that really separates someone who just likes Sherlock Holmes from a dyed-in-the-wool enthusiast.

How did you become a Sherlockian?

When I was seven I used to take swimming lessons at the University of Minnesota. My mom found an abridged audiobook collection of Holmes stories at our local library, including “The Speckled Band” and “A Scandal in Bohemia”, and started playing them to me in the car to and from my lessons. I can’t really pinpoint now what drew me so much to the stories, though it was probably some combination of the crime, the historical period, and the character of Holmes—after that I was completely hooked and wanted to hear the audiobooks over and over again. My mom encouraged me to talk to my grandpa, who had a big leatherbound collection of the entire canon with the Paget illustrations. I remember poring over that book when I was a kid—when we went to my grandparents’ house it was the first thing I went for. It was around then that I started building a small recreation of the 221B sitting room in a tiny basement closet, mostly out of construction paper taped to the walls and little antiques I’d found. That really deepened my interest and forced me to go over the stories again to find the small elements of the room that I’d missed.

I got connected to the world of Sherlockiana through Jake Esau, an actor in my local library circuit who would give performances as different literary or historical figures such as Edgar Allan Poe, P.T. Barnum, Dracula, and, of course, Sherlock Holmes. I showed up to enough of his events and asked enough questions about Holmes that he eventually got me in touch with Minnesota’s scion society The Norwegian Explorers. The people in the Explorers were extremely welcoming to an obsessive little eight year old—through them I started attending monthly meetings and deepened my love for the stories and the playing of “The Game”.

What is your profession and does that affect how you enjoy being a Sherlockian?

This fall I’ll be a senior English major at Carleton College, a liberal arts college in southern Minnesota. Being a college student primarily studying literature has fundamentally changed the way I approach the Conan Doyle stories—rereading them today I find that I’ve become equally interested in Conan Doyle’s prose style and the evolution of that style across the stories, as well as the different narrative structures he employs and what exactly makes them so effective. I think that my academic environment (and most across the country, I’d wager), is now very focused upon exploring if the conventional ‘literary classics’, most of which were written by well-to-do white men, are still relevant to readers and the study of literature in general. While I think that many are, and in no way consider Conan Doyle a concerning literary figure on the level of H. P. Lovecraft, I do think that there’s an interesting conversation to be had about what makes certain stories timeless and resonant even though some of their more unsavory elements (I’m looking at you, The Sign of Four and “The Adventure of the Three Gables”), exist, as well as the value in understanding works of art as products of their time, reflective of moral deficiencies that we may now balk at.

What is your favorite canonical story?

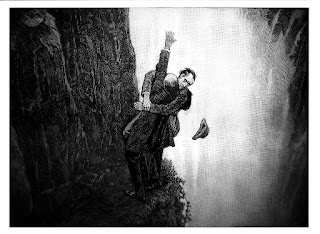

This is probably cheating but I’m going to include “The Final Problem” and “The Adventure of the Empty House” as one big story. In “The Final Problem” I love the character of Moriarty, a villain who actually has the mental power to undo Holmes, the canonically unique cross-country adventure through Europe, the near-cinematic confrontation at the Reichenbach Falls—one of the most iconic images in literature, I’d argue—and Watson’s absolutely heartbreaking final description of his friend as “the best and the wisest man” he has ever known. This story is just pure fun and the death of Holmes is such an unexpected left turn that when I read it for the first time I remember setting my book down and spending a good couple days actually thinking that that was the end.

I think the unconventionality of “The Final Problem” goes wonderfully with the more standard mystery of “The Adventure of the Empty House”, which brings the detective back to London and provides everything that I want in a classic Sherlock Holmes story—a seemingly-impossible killing, a late night stakeout, the bizarre trickery of the bust, and a wonderful second-in-command to Moriarty manifested in the odious Colonel Sebastian Moran, my favorite of Holmes’ antagonist after Baron Gruner. I also adore Holmes’ disguise as the book peddler, his reveal to a fainting Watson, the description of what really happened at Reichenbach (baritsu!), and everything the detective has gotten up to in the meantime. There’s so much juicy information here about Holmes’ character and I think the story portrays a deepening of his relationship with Watson that keeps me coming back, even though not a lot of deduction goes on in the case itself.

Who is a specific Sherlockian that you think others would find interesting?

Karen Murdock (ASH) is a really wonderful Sherlockian based in the Twin Cities—she is a longtime member of The Norwegian Explorers with a special interest in unique figures of speech found in the canon. This includes instances of hapax legomenon (in which a word is only mentioned once across the four novels and fifty-six short stories), assonant phrasings, anaphora (the selective repetition of a certain word), and much more. A lot of this work can be found on the online discussion group The Hounds of the Internet, of which Karen is a frequent contributor. On top of this she is one of the kindest, most generous people I know—when I was building my second 221B in middle school Karen would always come by to my house with old books she had picked up that she thought would be good additions to the room.

What subset of Sherlockiana really interests you?

This is probably obvious from my previous answers but I am especially interested in recreations of the 221B sitting room—this can manifest itself in maps, miniatures, sets for films and TV shows, and life-sized recreations built by enthusiasts. There is something about the realization of the iconic room and the unique interpretation that every creator brings to their space that I find thrilling—Conan Doyle peppers enough little inconsistencies and throwaway details through the canon to make the mapping of the place’s layout a scholarly project unto itself, which becomes as much about personal creative expression as an experiment in close reading.

As someone who has grown up being a Sherlockian, how has your activity in this hobby changed as you've grown?

I would say that the biggest difference between my early days of Sherlockian interest and today is that I’ve now known some of the people in the community for over a decade now, and thus feel a deeper connection to the social aspect of Holmes scholarship than I did in the past. I’m also at an age where I can independently go to conferences and meetings without forcing my poor parents to shuttle me someplace, as well as have a drink or two—at past conferences when I was a kid there was always a certain point in the night where I just had to go to bed, which isn’t the case anymore. As my abilities as a writer have improved I’ve also become more interested in actively contributing to Sherlockian scholarship, which I didn’t feel I had the chops to do in the past.

At the Lone Star Holmes conference, you gave a talk on Sherlock Holmes and psychogeography. Could you explain that term and how you linked Sherlock Holmes to it?

Psychogeography was a concept that one of my Carleton professors introduced me to—essentially it is concerned with the way an individual's environment, specifically within a city, consciously and unconsciously affects their behavior. Psychogeography has manifested itself in many different forms over the years but my professor specifically pointed me towards the work of the French scholar Michel de Certeau, whose 1984 book The Practice of Everyday Life has become a seminal text in the field. In one of the book’s essays titled “Walking in the City”, de Certeau argues that the modern city has become increasingly subjugated to the designs of governments and corporations who wish to find ever more subtle ways of controlling the citizenry and selling things to them. An example I gave at the conference of a non-de Certeauvian way of approaching a city such as London would be to instantly go to the Hard Rock Cafe in Piccadilly Circus, buy a couple of T-shirts, and then do everything else that appeared on the first google search of the best things for tourists to do in London. De Certeau likens this way of approaching a city to the view one gets of it from atop a skyscraper, which mutes the complex life happening on the ground below and makes the city seem conquerable, knowable to a single person and their worldview (which in reality it never can be, except maybe to Holmes).

In contrast to this approach, in his essay de Certeau outlines “tactics” of operating within the city that upholds ordinary human life and works as creative resistance against the all-controlling desires of companies and the state. Some examples of these are walking amidst a city’s people, taking shortcuts that are not officially mandated, and interacting with neighborhoods that are not commercially-driven and more representative of the life of the average citizen. In my talk I argued that Holmes derives his success as a detective from his awareness that true knowledge lies not from the view on a skyscraper (an overly-simplifying approach that I liken to Watson and Scotland Yard) but from being intimately attuned to a city’s people and its many neighborhoods, exemplifying de Certeau’s psychogeographic strategy. This, I argued, could be seen in the detective’s usage of the Irregulars and agents like Fred Porlock, his exploration of grimier London areas that most Victorian gentlemen wouldn’t dream of setting foot in, the moments where he acts as an unofficial arbiter of justice, and his unabashed love for all that is bizarre in human behavior.

What book would you recommend to other Sherlockians?

Maybe everyone has already read this but The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson is a magnificent piece of historical non-fiction that interweaves the story of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair with that of the serial killer H. H. Holmes, who constructed an elaborate “Murder Castle” during the time of the fair in which he disposed of and concealed his victims. Written like a novel and just as engrossing, this book serves as a fascinating insight into not only one of America’s first recorded serial killers but also the gargantuan accomplishment of the World’s Fair, an extremely ambitious project that was plagued with difficulty and represented America’s assertion of exceptionalism and innovation that would foreshadow Great Britain’s decline as the world’s leading superpower. This book not only checks the murder box for Sherlockians but is also very evocative of the late nineteenth century world that Conan Doyle so brilliantly captured in the stories.

Where do you see Sherlockiana in 5 or 10 years from now?

This is a very difficult question to answer. I am confident that the character of Sherlock Holmes will continue to connect with people in many different forms—through pastiches, television, movies, video games, board games, etc.—as he has done for over a century. I am also sure that social media will continue to connect like-minded Sherlockians across the world in new and exciting ways, promoting a dearth of possibilities for conferences and other events (Zoom, as annoying as it is, has really increased the opportunity for the accessibility of things like these). In modern pastiches and adaptations I think that we will see the characters in the canon further evolve in ways that are slightly (or extremely) different from their original portrayal in the stories, as so much of our modern understanding of them is also filtered through their representations in pop culture (for example, in recent years I think we have seen Holmes grow a little colder and more socially fringe than he ever was in the stories, with further emphasis on him being a form of a superhero, itself reflective of our Marvel/DC dominated media landscape). While some might view this as a form of blasphemy, what excites me is that people will still be interacting with these characters and coming up with new things to say about them. I am slightly worried about the future of the stories themselves—in my generation (I’m unabashedly counting myself as a victim of this), I think there are fewer people who go to books as their primary source of entertainment, especially those written in the nineteenth century. But if any stories survive they will be Conan Doyle’s, which remain so gripping that I’m shocked they’re as old as they are. Whatever happens, Holmes and his world of 1895 will remain an object of fascination and reinterpretation that I can’t wait to witness.

What a fascinating interview, and I love the photo with Les Klinger. I look forward to meeting you, Soren. And when you get out to Los Angeles, be sure to check out Chuck Kovacek's recreation of 221B. Everything on every shelf, and in every drawer has research and reason behind it. It's a delight. And his lovely wife will serve you tea while you visit!

ReplyDelete